In the past week (May 10-16), more than 83,736 alewife (also known as gaspereu) moved up the Milltown fishway located at the head-of-tide on the Skutik (St. Croix River) between New Brunswick and Maine. The Skutik and its watershed are at the heart of Peskotomuhkati Territory. Seeing the spawning

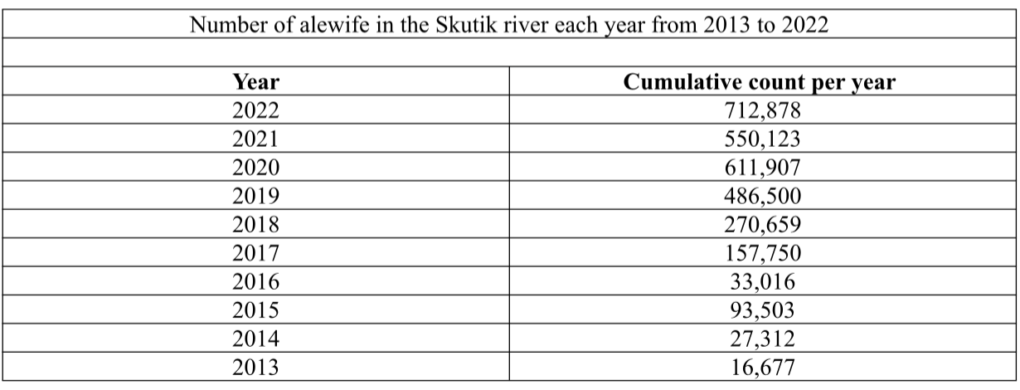

run off to such a strong start is a real cause for celebration, as much of the river was closed to this important and fascinating native fish until 2013.

This summer, the alewife community will be doing even better since the Milltown Dam will finally be removed, restoring Salmon Falls which has been covered by dams for over a century. This will allow alewife to have a lot more freedom to move up and down the river.

Alewife are considered a keystone species because of the critical role they play in both freshwater and marine ecosystems, acting as a feedstock for many groundfish (cod, polluck), mammals (whales, seals) and birds (puffins, eagles).

Historically the Skutik saw large runs of alewife. In 1851, Moses Perley, an avid sportsman and natural historian, noted that during the 1820s “alewife came in such quantities, that it was supposed they never could be destroyed.”

Starting in the 1820s, however, alewife moving up the Skutik faced-off against dams that were built without fishways. While fishways were added by the 1870s, pollution had created such a degraded environment that alewife numbers still remained low.

To help the alewife population continue to recover, the Conservation Council of New Brunswick along with a broad partnership led by the Peskotomuhkati Nation has long been advocating for, and implementing, fish passage improvements on the river.

A little bit of history

It wasn’t until 1981 that a mix of factors, including improved fish passage and restored spawning habitat, allowed the alewife to come back — and come back they did! By 1987, the Skutik was seeing runs of more than 2.5 million fish.

Then, in 1995, the State of Maine took action to close Skutik River under pressure from smallmouth bass fishing guides who believed that the alewife were harming smallmouth bass.

Research has since found there is no scientific evidence of this, as alewife and smallmouth bass coexist happily in thousands of watersheds around the world.

Nonetheless, the closing of the Skutik dropped alewife numbers to a low of 900 in 2002, undermining both the freshwater ecosystem of the Skutik and the marine ecosystem of Passamaquoddy Bay.

In April 2013 — after 18 years of alewife being blocked from more than 95 per cent of their historic spawning habitat — pressure from the Passamaquoddy Schoodic Riverkeepers, along with other environmental groups (including the Conservation Council of New Brunswick), led to both houses of the Maine legislature voting to open the Grand Falls fishway, returning the fish to large swathes of their historic habitat.

The most recent wave of restoration began in 2013 after this effective tri-national campaign to overturn a Maine State Law blocking alewife from migrating upriver. Over the past decade the Peskotomuhkati Nation and partners have developed a restoration plan, built highly skilled restoration teams and have carried out significant river restoration activities.

The restoration of Salmon Falls (though the removal of the Milltown Dam) is the biggest, most significant restoration action to date.

The significance of the restoration of Salmon Falls cannot be overstated. Next year alewife returning home to the Skutik will once again encounter Salmon Falls instead of a dam with a fishway.

Much work remains to be done, but with a major milestone like the removal of the Milltown Dam, the resolve of those dedicated to the present and future health of the Skutik is only strengthened.

Since the establishment of its Marine Conservation Program in 1990, the Conservation Council of New Brunswick has remained the leading authority on healthy ecosystems in the Bay of Fundy and marine environments along the coast of New Brunswick. We do this through a combination of rigorous research,

forging meaningful relationships Indigenous Nations and key groups such as fishers and fisheries associations, government agencies and departments, and coastal communities — and through the dedication of staff to achieve results over time.