[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Anatoxins from cyanobacteria have been confirmed to be responsible for a dog’s death in Fredericton this month

UPDATE: The provincial government has now confirmed the death of a Fredericton dog earlier this month was the result of neurotoxins created by cyanobacteria blooming in the Wolastoq (St. John River).

“I don’t want to inflame the situation or create too much concern if it isn’t warranted,” said Dr. Janice Lawrence, associate professor of biology at the University of New Brunswick, in a previous interview with the Conservation Council. “At the same time, we can’t wait until something really bad happens. We’ve already lost a few dogs.”

Certain strains of cyanobacteria, bacteria that’s photosynthetic, contain toxins and can cause skin irritations in the form of rashes, hives or skin blisters, and can result in illness among people and animals. An even smaller, less-well-studied group of the bacteria produce anatoxins, which bind to the neuro-muscular junctions of whatever ingests them, the researcher said.

“What that does is stop the muscles from working,” Lawrence said. “They go into seizures. They go into paralysis and suffocation because the respiratory muscles no longer function.”

Vomiting and diarrhea are two other common symptoms of the poison. Blue-green algae is another common name for cyanobacteria, despite not being a species of algae.

In the spring, the professor and her team began sampling the river between Carleton Park, located on Fredericton’s north side, and upriver to the Mactaquac dam, immediately finding areas where anatoxin-producing cyanobacteria were present.

Last year, three dogs died suspiciously close to each other and were linked to anatoxins.

Dr. Jim Goltz, manager of New Brunswick’s Veterinarian Laboratory and Pathology Services, said out of the dogs that died last year, his team only received one for necropsy. That makes it difficult to determine for certain whether cyanobacteria was the cause of death in all three cases, he said.

And for the one dog Goltz was able to study, the cause of death recorded wasn’t cyanobacteria toxicity. A pre-existing malignancy ruptured and the dog bled to death, he said.

A fourth dog died in 2010 as a result of anatoxins, but Goltz said the dog’s movements prior to its death creates uncertainty about whether cyanobacteria in the Wolastoq was responsible.

“There’s always a risk of making generalizations,” Goltz said. “Problem is, once there is an issue, then everybody always suspects that’s responsible for everything.”

Still, the dog rushed to a local veterinarian office Saturday died within 20 minutes of first showing symptoms, the public official said.

“It had just learned how to swim,” Goltz said about the puppy. “(The dog was) very excited by that. Went into the water a couple times and when it came out of the water a second time, it vomited. Then it kind of became wobbly on its feet. Then it collapsed.”

Lawrence’s research hopes to find where the deadly material gathers in underwater microbial mats, before it tears off and floats away. Most people are familiar with the free-floating blooms that can cause rashes, she said, but it’s these underwater collections of cyanobacteria that produce neurotoxins.

She’s following evidence the bacteria the dogs seemingly consumed originated near the bottom of the river, on mud flats and attached to aquatic vegetation.

“To get an idea of the extent of them, what they look like and where they might have come from,” she said.

Organizations like the Nashwaak Watershed Association were contacted by Lawrence and have also found the gene needed to produce anatoxins in the bacteria collected in water samples taken from the Nashwaak River.

Now the professor believes cyanobacteria has collected enough biomass in places to lift off the river’s bottom and float downriver when boats or other disturbances pass by.

“And because this is a flowing environment, these things move,” Lawrence said.

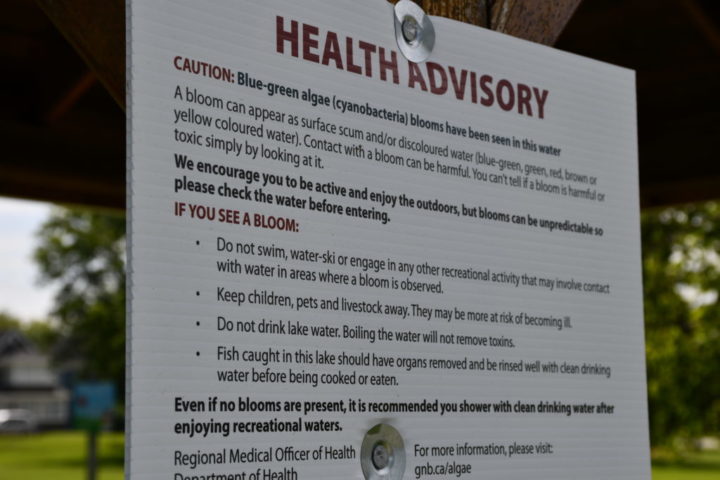

While pet owners and swimmers alike often know to avoid large batches of the bacteria, the small amount of anatoxins required to cause harm means people should take precaution around even seemingly safe areas.

Goltz also believes people need to take precautions.

“These reports shouldn’t prevent people from going outside to enjoy things,” he said. “But it’s important to understand risks and take steps to reduce risks.”

He said in addition to the regular checks people should do to ensure their swim is safe – watch for strong currents, sharp rocks and broken glass – people need to check to see if the water looks clean and smells good. People also need to watch children and animals who can’t watch themselves and avoid swimming with cuts or open wounds.

Making sure one’s pets are hydrated before going to the beach can discourage them from drinking the water there.

“When you come out, make sure to rinse with good, clean water,” he said.

When asked on a CBC Information Morning Q&A segment if Dr. Lawrence would swim in the Wolastoq or at the Mactaquac beach right now, she said she’d have to take extra precautions to feel safe. She’d prefer to jump into open water from a boat rather than wade in from shore, and would rinse thoroughly with clean water afterwards and wash her hands with soap before eating anything.

Although blue-green algae occurs naturally, a bloom can also be triggered by pollution in a body of water, such as phosphorus – a common nutrient in our day-to-day lives.

Lawrence says only some forms of cyanobacteria need high quantities of nitrogen to survive but all require phosphorus.

“Cyanobacteria, as a large group, tend to do well where there’s larger phosphorus loads. They’re also capable of taking up extra nutrients more rapidly than their competitors,” she said.

In our new report on climate change and public health, released June 25, researcher Dr. Louise Comeau found communities across New Brunswick will experience a two-to-three fold increase in 30+ C days over the next three decades. In Fredericton, climate data projections show the city could experience at least 20 days of more than 30+ C heat, up from the 1976-2005 average of eight.

The microorganisms found in the Wolastoq are also unaffected by the speed of currents, unlike other cyanobacteria.

The researcher said she became concerned after not hearing strong warnings from public health authorities about the river following the dog’s death. She believes the public needs to be aware of the risks posed to animals and small children, especially since the underwater sources of the algae-looking material are still unknown.

“I think the important thing is providing as clear information as we can that this is a different scenario than we’ve seen in the lakes. It’s different than what we’d heard of before. People need to be aware of that when making decisions to spend time recreating on the water, until we have better guidelines we can provide everyone,” Lawrence said.

“And that’s going to take a while to develop.”

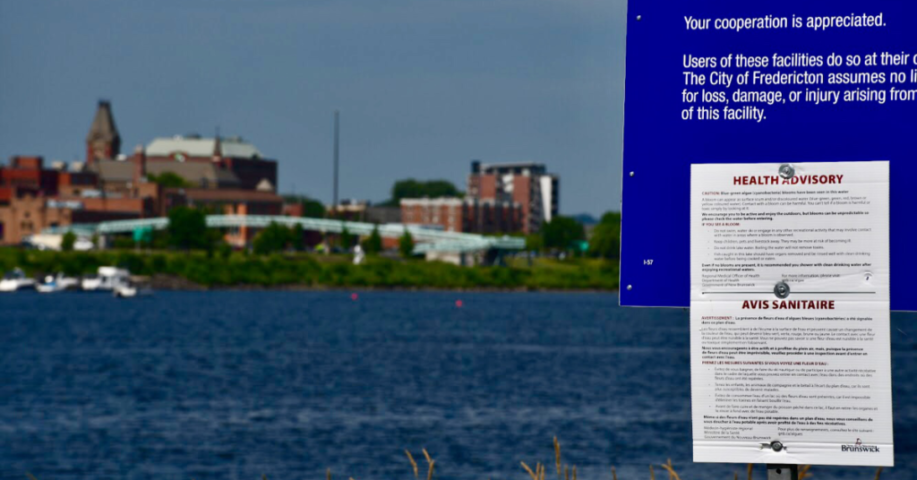

The provincial government now includes the section of the Wolastoq between Woodstock and Fredericton in its blue-green algae public health advisories and alerts section of its website.

Recommended links:

- Blue-green algae: here’s what you need to know

- Climate change to cause more blue-green algae outbreaks, UNB biologist says

- Let’s talk about phosphorus and blue-green algae

- Blue-green algae in New Brunswick lakes

- Check the Government of New Brunswick’s public health advisories and alerts

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]