One of the world’s largest tailing dams is proposed to be constructed in the upper Nashwaak River Valley as part of the proposed Sisson mine operation. With catastrophic mine waste spills on the rise and the fact that the Sisson mine’s permitting process did not adequately examine the possibility of a tailings breach, there is reason to worry about the future of the Nashwaak Watershed.

Jacinda Mack says that the lives and landscape of the Secwepemc territory in the heart of British Columbia forever changed on August 4, 2014, the day the Mount Polley tailings dam breached. Mack was the Natural Resources Manager for the Xat’sull First Nation when 25 million cubic metres (10,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools) of contaminated process water and tailings poured into Polley Lake, Quesnel Lake and eventually the Fraser River Basin.

Before the Mount Polley disaster, Xat’sull families harvested and processed up to 200 salmon per family. The Quesnel Lake watershed supported a lucrative sport and commercial fisheries and tourism industry while also being home to resource extraction in the form of mining and logging.

For the losses suffered by the worst mine waste spill in North America’s history, the Xat’sull First Nation at one point received tins of salmon to compensate for the loss of wild salmon contaminated by the spill. The company that operates the Mount Polley mine and tailings dam, Imperial Metals, was never fined by the B.C. government.

“Tons of toxic substances were dumped into waterways. Fish habitats were destroyed. People’s drinking water was affected. Yet, nearly three years after the disaster, and despite clear evidence of violations of Canadian laws, no charges have been brought forward by any level of government. This is wrong, simply wrong. It sets a terrible precedent for other mines across the country, let alone internationally,” said Ugo Lapointe, Canada Program Coordinator for MiningWatch Canada. The organization is taking the B.C. government and Mount Polley Mining Corporation to court for violations of the Fisheries Act in relation to the Mount Polley disaster.

B.C. made some amendments to its mining code in response to recommendations made by an inquiry into the Mount Polley disaster but Mack, now the coordinator of the First Nations Women Advocating Responsible Mining, argues that the changes are not strong enough to prevent another disaster.

David Chambers, a mining technical specialist with the U.S.-based Center for Science in Public Participation, maintains tailings disasters are on the rise and advocates against the construction of new tailing dams. According to the report he co-authored, “The Risk, Public Liability, and Economics of Tailings Storage Facility Failures,” half of serious tailings dam failures in the last 70 years (33 of 67) occurred between 1990 and 2009. Eleven catastrophic failures are predicted globally from 2010 to 2019. The average cost of these catastrophic tailings dam failures is $543 million, according to Chambers’ report.

While the industry says that they are working on best practices for tailings dams, catastrophic mine waste spills are increasing in frequency, severity and cost because of, and not in spite of, modern mining techniques. The tailings dams are getting larger and are not subjected to proper regulations.

Mining is essentially a waste management industry, says Joan Kuyek, founder of MiningWatch Canada. Kuyek argues that mining has short-term benefits and long-term consequences. What to do with the large amounts of waste generated from the mining of ore has always been a problem and the problem is getting worse with the mining of low grade ores that generate even more waste and require even larger dams or storage facilities. The increasing rate of tailings dam failures is directly related to the increasing number of larger tailings dams.

Mining companies dump tailings, the waste left over after ore has been mined and processed, into dams for permanent storage because it is cheaper than other methods that are considered less risky to the environment such as the dry-stack tailings method.

Knowing all we know about the risks associated with today’s tailings dams, one has to wonder whether we will be telling stories of the day the Sisson tailings dam breached and devastated the Nashwaak River?

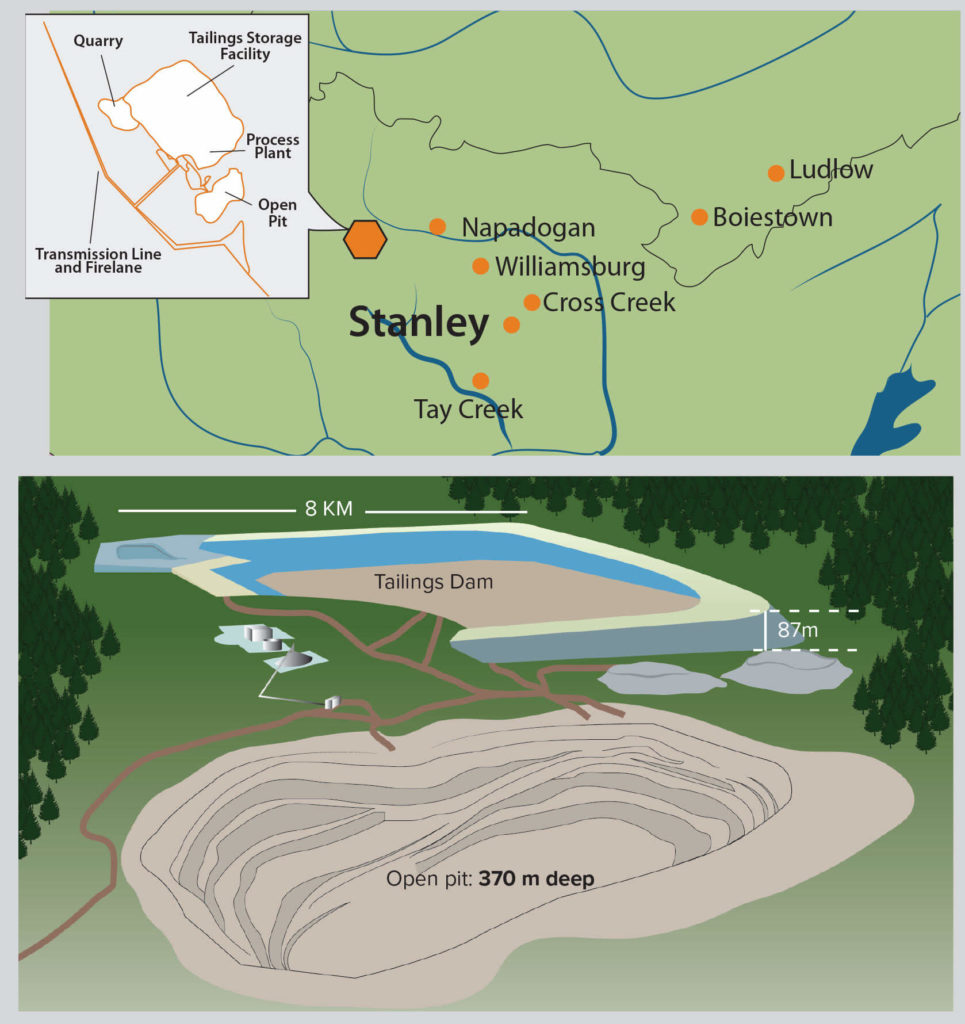

Lawrence Wuest, a resident of Stanley, has worked diligently to reveal the impacts of what could be one the world’s largest open-pit tungsten and molybdenum mines. The Sisson mine, owned by Northcliff Resources and Todd Minerals, is located about 30 km from Stanley and 60 km northwest from Fredericton. The operation would have a footprint of approximately 1,250 ha, including a 145 ha open-pit that is 370 m deep and a tailings dam estimated to be 87 m in height at its deepest point and 8 km in length. In comparison, the Mactaquac dam is about 40 to 50 m in height and 0.5 km long.

According to Wuest, if a tailings breach were to occur at the Sisson mine, the volume could be four times more than that spilled at the Mount Polley site. If the tailings dam did fail, according to Wuest, the tailings would travel down the Nashwaak River and reach Stanley in 17 to 18 hours and Fredericton in three days.

The Conservation Council brought together experts to examine and comment on the mine’s environmental assessment reports. Based on the experts’ assessment of the project and environmental assessment, the Conservation Council argues that the Sisson mine should not be approved. Important questions about the mine’s impact on the natural environment remain unanswered.

The Canadian government announced approval of the mine’s environmental assessment based on the company meeting conditions on June 23. Previously, in 2016, the New Brunswick government approval of the mine’s environmental assessment based on the company meeting 40 conditions. However, information on how the mining company is going to address those 40 conditions has not been made public, forcing the Conservation Council to file a Right to Information request.

When Ministers responsible for mining from provinces and territories across Canada meet in St. Andrews, New Brunswick this August, it will be a time for us all to demand that our watersheds are protected from being forever devastated by a mine’s waste.