The Nashwaak watershed is a vibrant network of rivers, streams and tributaries flowing 110 kilometres across central New Brunswick, from the Upper Nashwaak Lake below Juniper to the St. John River in Fredericton.

For generations, families living in communities between these points, from Napadogan to Stanley, Taymouth to Marysville, have flocked to the banks to swim, fish, paddle and, of course, pick fresh fiddleheads.

It’s this legacy that is top of mind as we celebrate World Water Day (March 22), and it’s what inspired more than 200 people to show up at a recent consultation to ask questions about the future of the waters they love.

Residents attended the March 15 meeting in Cross Creek to hear from the federal government and the Sisson Partnership about the latest step in the Sisson Mine project, a proposal to build a large open-pit metals mine and tailings dam on public land at the headwaters of the Nashwaak, near Juniper, Napadogan and Stanley.

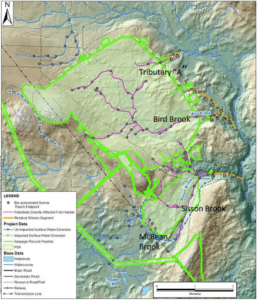

The partnership, comprised of Northcliff Resources and Todd Minerals, is applying for permission to dump mining waste into portions of fish-bearing waterways, destroying Sisson Brook and significantly affecting parts of McBean Brook, Bird Brook, Lower Napadogan Brook and an unnamed tributary to the West Branch of Napadogan Brook

The Sisson operation would have a big footprint, covering approximately 1,250 hectares of public land, including a 370-metres-deep open pit and a tailings dam the partnership estimates would be up to 90-metres tall at its deepest point and 8 kilometres long — twice the height and 16-times the length of the Mactaquac dam.

Experts reviewing the partnership’s documents see no evidence the project has gone through a rigorous scientific review, and the companies have not given residents a detailed design for the dam that would hold back the approximately 282 million metric tonnes of tailings waste the mine would produce over its 27-year operation.

Not that those plans would give much comfort.

The partnership is proposing to use for Sisson the same old-fashioned way of dealing with waste that mines used 100 years ago, the same system that failed at British Columbia’s Mount Polley mine four years ago, sending 24 million cubic metres of toxic slurry thundering into pristine waters and the home of a quarter of the province’s sockeye salmon population, and the same system that led B.C.’s Mount Polley Independent Expert Engineering Investigation and Review Panel to say it “firmly rejects any notion that business as usual can continue.”

The company behind the Mount Polley breach was never charged and paid no fines. The impact of the spill affects the local environment, communities and First Nations to this day.

B.C. didn’t have the resources to handle the Mount Polley spill — equivalent to 10,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools of tailings containing dangerous pollutants such as lead and arsenic.

How can we reasonably expect New Brunswick to deal with a breach that could send an even greater volume of mining waste into the Nashwaak watershed, the St. John River, and communities downstream to the Bay of Fundy?

New Brunswickers can have their say as the partnership seeks permission to impact fish-bearing waters in the region. You can weigh in on the partnership’s plan by submitting comments to Environment and Climate Change Canada at ec.mmer-remm.ec@canada.ca until May 3, 2018.

Something very important happened at the meeting in Cross Creek.

Residents said they know their region needs jobs, but that those jobs weren’t worth the risk of losing the rivers where they’ve raised their families.

What they were saying, and, I think, what we should all say with them, is that we’re too lucky here in New Brunswick to have the abundant freshwater resources we do — especially looking at so many countries suffering for lack of water — that it’s not prudent or smart to risk such a valuable asset, and an asset that will only get more valuable in years to come.

The residents gathered at Cross Creek were saying that we need to build an economy that puts water protection at the forefront. On World Water Day, and every day, we’re with them.