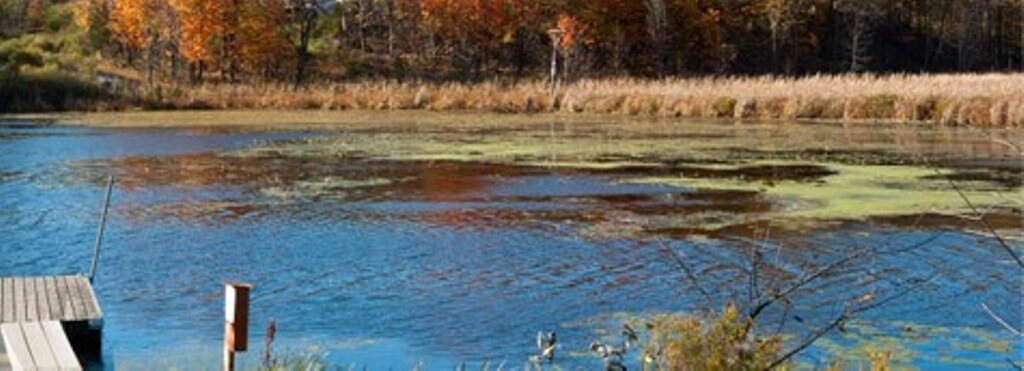

Blue-green algae on a New Brunswick lake. Source: 2gnb.ca

Blue-green algae on a New Brunswick lake. Source: 2gnb.ca

While a number of New Brunswick lakes have had persistent blue-green algae challenges, last summer we saw a spike in the number of lakes added to the Department of Health advisory list, including outbreaks in well-populated lake watersheds, relatively undisturbed lakes, and surface water supplies providing drinking water.

Since 2010, the Canadian Rivers Institute (CRI) has been investigating the growing issue of cyanobacterial outbreaks in NB lakes. This increasing concern has prompted the CRI to define a three-pronged approach to tackling this growing problem in the province. In a partnership with community-based lake associations and the Department of Environment, the CRI will undertake local water quality monitoring, continue its scientific program to understand conditions specific to NB algal blooms; and help deliver an educational program for local lake users.

Blue-green algae is actually a bacteria (cyanobacteria) that can grow in large quantities when exposed to the right mix of conditions such as warming temperature, low water levels or an input of nutrients. Blooms range in colour from dark green to yellowish brown and can produce toxins which can be cause for health concern particularly where lakes are used for swimming and drinking.

Blue-green algae is actually a bacteria (cyanobacteria) that can grow in large quantities when exposed to the right mix of conditions such as warming temperature, low water levels or an input of nutrients. Blooms range in colour from dark green to yellowish brown and can produce toxins which can be cause for health concern particularly where lakes are used for swimming and drinking.

“Generally, input of nutrients, particularly phosphorous, into lakes is causing blue-green algae blooms. However, the range of lake types in NB appear to be responding differently to our changing climate, says Dr. Allen Curry, a CRI science director at the University of New Brunswick, and the lead for the NB lakes blue-green algae study.

As part of this next phase of work, CRI will continue sampling and characterizing the plankton communities (the very small organisms drifting or floating in the water column) in the affected NB lakes and build computer models that can help define specific conditions for algae-prone lakes. The Department of Environment and Local Government (DELG) will continue its annual sampling of lake water chemistry, temperature, and dissolved oxygen profiling.

“We don’t yet know all of the mechanisms leading to harmful algae blooms in our lake ecosystems but we do know that dynamic physical elements such as wave action, heating, precipitation, sedimentation and even future climate change projections can also contribute to blooms in low nutrient lakes, such as we have in New Brunswick,” he says.

Together the CRI, DELG and lake groups will deliver presentations for lake users and develop and test a “rapid phosphorous response” kit that will help community groups set up citizen-science programs to increase the local engagement and the capacity to monitor local algae outbreaks.

“We are at the beginning of our challenge to understand cyanobacterial blooms in NB lakes and this research will start to produce the long-term data and targeted studies that are needed to pin-point the landscape characteristics and the impacts a changing climate has on our waters. From there we will be able to develop more effective management strategies for dealing with this public health concern,” says Curry.

An advisory does not necessarily indicate a toxic water situation but allows the public to become more aware to look for the formation of highly visible blooms and scum, which pose the most risk.

In recent years the lakes on the NB Department of Health blue-green algae advisory list has included: Wheaton Lake, Washademoak Lake, Grand Lake, Harvey Lake, Chamcook Lake, Lake Utopia, Lac Baker, Lac Unique, Irishtown Nature Park, Mapleton Reservoir, Camp Lake and Bathurst Lake.