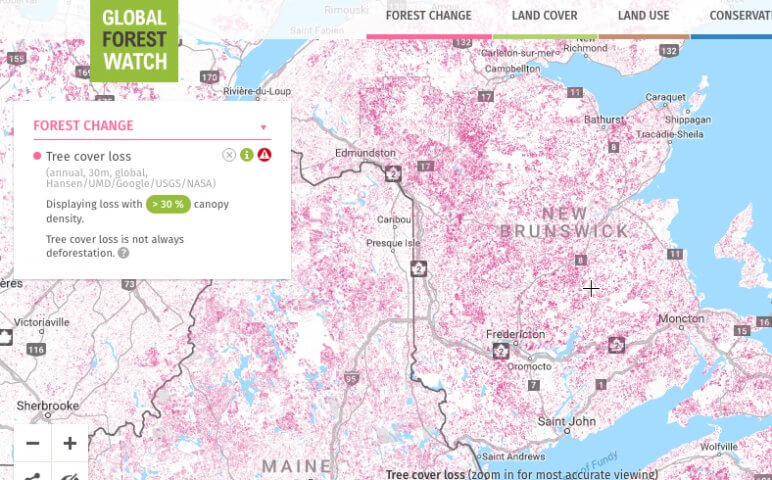

Forest loss in the headwaters of Miramichi’s watershed is happening and warrants our attention, according to a study released in January 2017 in the highest-ranking scientific journal on remote sensing.

The article assesses the accuracy of annual forest loss data from global satellite imagery (publicly accessible through Global Forest Watch) across 8,520 square kilometres of public lands in the Miramichi River basin from the year 2000 to 2012. The Miramichi River basin covers one-quarter of the 73,000 square kilometres of New Brunswick’s land base. The scientists used forest harvest inventory data made available from the Department of Natural Resources (now the Department of Energy and Resource Development) to assess the accuracy of the forest loss dataset and found it to be quite reliable when applied to clearcut mapping in the temperate forest region of Miramichi.

The article assesses the accuracy of annual forest loss data from global satellite imagery (publicly accessible through Global Forest Watch) across 8,520 square kilometres of public lands in the Miramichi River basin from the year 2000 to 2012. The Miramichi River basin covers one-quarter of the 73,000 square kilometres of New Brunswick’s land base. The scientists used forest harvest inventory data made available from the Department of Natural Resources (now the Department of Energy and Resource Development) to assess the accuracy of the forest loss dataset and found it to be quite reliable when applied to clearcut mapping in the temperate forest region of Miramichi.

The study by Julia Linke et al. published in Remote Sensing of Environment also summarizes the annual forest harvest in each of the sub-watersheds of the Miramichi, as well as the forest harvest rates on licensed Crown land and industrial freehold land in that area. Industrial freehold located near the headwaters of the southwestern Miramichi had the highest harvest rates, leading the authors to call for monitoring and impact assessments of that area.

The 2017 study notes that Miramichi’s forest is dominated by red spruce, balsam fir, yellow birch, sugar maple as well as tree species that are in decline in the region such as white pine, eastern hemlock, eastern cedar and beech. Four large Crown land licence holders operated on Miramichi’s public lands in the studied period: the provincial government (in a licence previously held by Weyerhaeuser), Fornebu (previously UPM Kymmene), J.D. Irving Ltd. and Twin Rivers (previously Fraser Paper Nexfor). Only approximately 2.6 per cent of Miramichi Crown land was catalogued as protected. The Miramichi River basin study area also included 2,586 square kilometres of land managed by industrial freehold, 89 per cent of it by J.D. Irving Ltd., and 2,110 square kilometres of private land.

The high harvest rates on industrial freehold in the Miramichi watershed is of further concern given that J.D. Irving asked the provincial government in 2012 to have all Crown land in New Brunswick managed as J.D. Irving freehold. The proposal was only made known to the public through a sweep of the provincial archives by the Halifax Media Co-op and the NB Media Co-op.

How satellite imagery is revealing serious forest loss next door in Nova Scotia was the subject of an opinion piece by Donna Crossland, a biologist who holds a Masters of Science in Forestry from the University of New Brunswick, in the Chronicle-Herald on Jan. 17, 2017. Crossland pointed out why we should be concerned about forest loss: “Forests take decades, and in some cases centuries, to grow back, especially tree species of higher value that prefer shade and naturally achieve large sizes.”

The Conservation Council produced a video in 2014 and brought to the media’s attention in 2012 how this newly available satellite imagery was showing that New Brunswick was no longer home to large intact forest areas, outside of the province’s three-per cent protected forest areas.

New Brunswick’s Auditor-General Kim MacPherson noted that 80 per cent of all the wood harvested from New Brunswick’s Crown forests in the past two decades has happened through clearcutting in her 2015 report and recommended that forest management decisions be based on science.

The recent scientific study by Linke et al., validating satellite data of annual forest loss in the Miramichi watershed while also noting the most severe forest loss in the headwaters of the Southwestern region of Miramichi, highlights the urgent need for considering the impact that pervasive clearcutting has on water quality and aquatic species of the Miramichi River to help guide future management and conservation efforts and align them with New Brunswickers’ priorities regarding forest values.